When Resident Evil was first unleashed upon the gaming world in 1996, few people could probably imagine the tumultuous struggle with identity into which the series would eventually descend. In many ways, Resident Evil was the quintessential product of its generation – a game whose design was very much informed by the technical limitations of Sony’s first Playstation. As the series and the hardware upon which it appears have evolved, so have the foundational elements of the series. The quality of the character models has risen significantly, fixed viewing perspectives have given way to a fully player controlled camera, and the detailed yet flat pre-rendered backgrounds have long since given way to fully three-dimensional environments. Yet despite the technological advances the series has adopted, Capcom’s design teams have become increasingly conflicted regarding just what constitutes an “authentic” Resident Evil experience, in terms of both gameplay style, and the genre within which it sits.

Anybody familiar with Resident Evil as a series will be well aware of the tropes of the older games; periods of exploration punctuated with the occasional boss fight, all leading toward the inevitable battle where the protagonist is provided with a weapon powerful enough to dispatch the end of game boss once and for all. It is an understated yet appreciable way for a game in this genre to progress, ultimately rewarding the player for being able to survive just long enough to have beaten the odds. As such, dramatic change has never really been needed, whether or not Capcom has attempted to implement it, yet change has been so rapid it has left the franchise without a discernible identity.

For some, it is the eloquent design and style of these early games (and the excellent Gamecube remake) that represent the pinnacle of what the series has to offer, both in terms of design and visual aesthetic; but for others, the fundamental changes to the control system, and the shift to third person combat popularized by Resident Evil 4 remains the defining entry in the franchise. Yet the juxtaposition of these two stages in the series’ evolution also highlight what seems to have proved the most troublesome issue for Capcom to overcome in developing Resident Evil 6. Should the franchise stay faithful to its roots, or should it expand and grow away from what has come before?

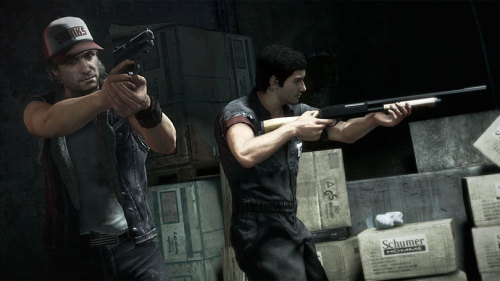

Arguably the biggest problem hampering the franchise with RE6 is its lack of oppressive atmosphere for which many of the earlier entries were famous. The most obvious manifestation of this is the continued implementation of cooperative play first introduced in Resident Evil 5. Though the Resident Evil series has always offered gamers a narrative that encompasses several primary characters, the limited nature of their interactions has allowed the series to remain focused on the player character, and their solitary explorations. However, the increasingly intrusive supporting cast members and their largely persistent presence onscreen alongside the main character (as seen in RE0, 4, 5, and now, 6) has been a largely detrimental element to the series. While cooperative play may seem to be increasingly valuable in a world of burgeoning multiplayer suites, tonally it is entirely antithetical to the style of the survival horror genre. The tangible sense of dread created by facing insurmountable odds alone is just as important to the genre as the gameplay mechanics – a fact that Capcom seems to have forgotten in their concession to the conventions of gaming modernity.

As a series which has been extremely cinematic since its earliest entries, it is unfortunate to see the horror aspects of the game eroded in such a way. The damage that an additional character causes to both the dramatic structure and the visual mise-en-scene of a survival horror game is twofold. Firstly, it can destroy the sense of loneliness within the exploration of the game world for which the series is famous. Secondly, it also lends a sense of empowerment that undermines the stressful nature of being that lone survivor trapped in a situation substantially bigger than them. It is precisely these kinds of deviation from the tropes of the survival horror genre which contribute greatly to the games conflict of identity. In the case of Resident Evil, a horror shared is a horror neutered.

This deviation from genre is not helped in the least by the numerous vehicular sections that Capcom have woven throughout the story. At best, these additions offer short breaks from the series typical gameplay, at worst, they make it difficult to suspend your disbelief in the narrative, when sequences such as these have been seen and done before, in a variety of other modern titles. While car chases, motorcycle getaways and fighter jet battles might seem appropriate in a globe-trotting viral outbreak adventure, they merely serve to further distance the game from survival horror, and plunge it into the clichés of the action genre. The levels of visual excess on display during some of these set pieces are sadly representative of the scope of mimicry present in the gaming industry at large. In a world where games like Call of Duty and Battlefield struggle for the dominant market share, it makes sense that Capcom would try to capture elements of what gamers find so appealing about the modern shooter. Unfortunately for Capcom, the irony here is that they seem unable to recognize in these other (more successful) franchises exactly what they are trying to break away from with their own series – familiarity. Most of today’s popular games have never attempted to reinvent the wheel (nor do they seem to have this intention for the future), they merely continue to grease it when necessary

I have no doubt that Capcom, with enough determination; can reclaim the survival horror crown that they so successfully forged in 1996. Unlike the awkward melding of styles on display within Resident Evil 6, the franchise’s future success will pivot on a unified vision for the series. Reduce the narrative scope, once again letting players creep through the nightmare alone, and most importantly, have confidence enough in your own product to resist reproducing elements of other popular genres. If future developers on the series can do this, then horror (and the gamers that appreciate it) might, just might, once again begin to reside in the mansion that Capcom built.